Fraser (my co-host over at Astronomy Cast) and I like to joke about how everything we know in astronomy we know because of the Cosmic Microwave Background. How do we know the universe formed during the Big Bang? The CMB. How do we know the cosmic geometry is flat? The CMB. How do we know the mass distribution of the Oort Cloud? The CMB. How do we know where babies come from? The CMB.

Fraser (my co-host over at Astronomy Cast) and I like to joke about how everything we know in astronomy we know because of the Cosmic Microwave Background. How do we know the universe formed during the Big Bang? The CMB. How do we know the cosmic geometry is flat? The CMB. How do we know the mass distribution of the Oort Cloud? The CMB. How do we know where babies come from? The CMB.

Okay, so that last one is an exaggeration. As far as I know, human babies and the CMB have nothing in common. The remark about the Oort Cloud, however, may not always be as far fetched as it sounds. A group of scientists working at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, and lead by David Babich, have theorized a new technique for determining the mass distribution in the Oort cloud using distortions in the Cosmic Microwave Background.

According to the theories of Babich and his team, if you observe the light of the CMB through the Oort cloud, the intensity you detect is related to both how much CMB light is blocked by Oort cloud objects (which are so small and so far away that you can look through them the way you look though a cloud of fine dust), and to how much light the Oort cloud objects emit at the color being observed (in this case, the dust you are looking though is made of glow in the dark paint). If the Oort cloud isn’t symmetrical, any distortions may be visible as anisotropies in the light of the CMB.

The key to understanding this result is understanding that warm objects give off light in a variety of colors. The hotter an object is, the shorter the wavelength of the light – the bluer the light. The colder an object, the longer or redder the light will be. Humans, for instance, give off the most light in infrared. That doesn’t mean we give off all our light in any one specific wavelength of infrared. Rather, we give off most of our light in one shade of color, but there is light of a variety of colors coming from our warm bodies, even in the darkest of rooms (although some colors, like green, aren’t emitted in numbers enough higher than zero to matter).

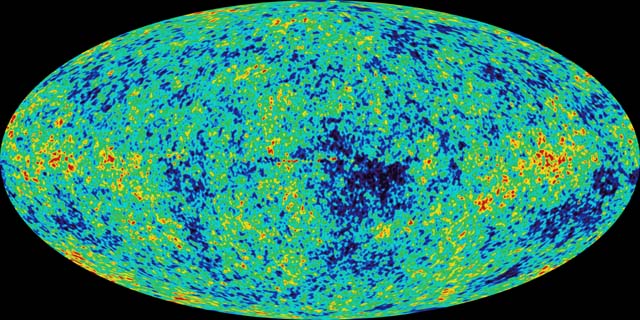

The CMB is basically a perfect black body with a temperature of 2.728 Kelvin. It is located at essentially infinity in all direction. It is a perfect background light. This team theorizes that objects in the Oort Cloud should have temperatures related to their distances, such that an object at 1000 AU would have a temperature of 8.5 K and nearer objects would be hotter while farther objects are colder (think of the temperatures of rocks illuminated by a camp fire. The same physics describes the heat of the rocks and of the objects in the Oort Cloud. These temperatures are very similar, and the same technology that can be used to detect the CMB will also detect the heat signature of Oort cloud objects.

So, while the 2.728 K CMB and 8.5 K Oort cloud objects both emit microwave light, the light doesn’t peak at the exact same color, although there is overlap. Despite the amazing precision that WMAP and other missions have already mapped the CMB, their accuracies weren’t sufficient to test this theory, but this is something that future missions, like Planck, may be able to. Any distortions in the Oort cloud that are found will point to past encounters with stars. As our Solar System passes near other stars on its orbit through the galaxy, the Oort cloud gets distorted and these distortions trigger long period comets.

Good theories, in my mind, are defined as theories come in to forms. There are those, relativity, that put existing observations together in a new way that leads to deeper understanding and understanding of previous mysteries, while also making predictions. There are also good theories that look at the universe and apply existing knowledge to predict future discoveries we can’t get to through more common means. This set of papers falls in that second category. This isn’t theory for the sake of pretty math – this is theory that defines how to build a better mouse trap.

When I first read the article and saw the phrase Oort cloud, I assumed you were talking mainly about the proximate source of long period comets. I was going to ask how big a role heating from nearby stars and escaped comets from distant stars played in the teams calculations. But then, rereading the article I see that you use “Oort cloud” to mean 1000 AU from the Sun instead of say 100 times farther out. ( That 1000 AU figure occurs just before you messed up the discussion of temperature. ) So these days everything beyond Eris is the Oort cloud. Even objects whose orbits are stable against perterbation from distant stars. Fine. But doesn’t Harvard boy realize that his lack of precision gives up a potential opportunity to name a vast region of the solar system after himself.

Actually I think it would very exciting if they could find some quirk in comet distribution in the 1000 AU range. It would likely be evidence for a distant planet. Except we won’t be allowed to call it a planet. Because the Priests of Prague have proclamed that a planet has to clear its orbital neighborhood, and a distant planet-massed object would have the effect of cluttering the far outer solar system with debris that Jupiter would otherwise have tossed to interstellar space.

And does the Oort cloud actually block a significant amount of radiation at any frequency?

According to the paper, “Long Period Comets (LPC) associated with the Oort Cloud originate in its outermost reaches because objects with large semi-ma jor axes can be preferentially ejected into the inner Solar System. The observed aphelia of LPCs place the outer limits of the Oort Cloud at a distance of approximately 25000 AU (Oort 1950; Marsden & Sekanina 1971), while simulations of the Oort Cloud’s formation, assuming that the Sun formed in a star cluster, suggest that a significant amount of mass may lie in an inner Oort Cloud, which is located at 1000 AU (Hills 1981; Fernandez 1997; Dones et al. 2004). To this point, we have no methods capable of detecting smaller objects in the Kuiper Belt or any objects in the inner Oort Cloud.”

I’m willing to just use the adjectives used in the paper. Eventually, maybe, the IAU will come up with strict definitions. We’re not there yet, so Oort owns everything according to Babich.

The paper doesn’t say exactly what fraction of light the Oort cloud blocks. They give an equation for how it would be blocked in the paper above as well as this one, as a function of optical depth and temperature.