In case you haven’t heard, on January 9, 2008, astronomer Edo Berger (working with Alicia Soderberg) noticed something fuzzy emerge in fresh Swift data, and that something fuzzy turned out to be the first supernova ever caught in the act of exploding. This discovery is fabulous for a variety of reasons. First off, there is the “Oooo, Cool Explosion” factor inherent in Supernovae, and it is particularly cool because it was watched from moment 0. Second, it is uber cool because this observation confirms several theories on how supernovae function (and also probably rules out several lesser theories). So, explosions and cool science all in one. What more can a girl ask for?

In case you haven’t heard, on January 9, 2008, astronomer Edo Berger (working with Alicia Soderberg) noticed something fuzzy emerge in fresh Swift data, and that something fuzzy turned out to be the first supernova ever caught in the act of exploding. This discovery is fabulous for a variety of reasons. First off, there is the “Oooo, Cool Explosion” factor inherent in Supernovae, and it is particularly cool because it was watched from moment 0. Second, it is uber cool because this observation confirms several theories on how supernovae function (and also probably rules out several lesser theories). So, explosions and cool science all in one. What more can a girl ask for?

How about a new standard way to find Supernovae? That is also what this represents.

Here’s what happened

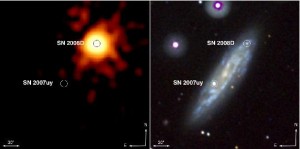

In the not so distant galaxy NGC 2770 (90 million light years away), a supernova went off as a New Year’s present to astronomers. Named SN2007uy, this happy little Type Ib explosion represented the death of a giant star, perhaps a Wolf Rayet, that decided it was time to stop burning fuel and collapse into a black hole. While not generally useful as standard candles, these explosions may in some cases lead to gamma ray bursts, which some folks are trying to turn into standard candles. And they’re kind of the most amazing explosions still going on regularly, and that alone makes them cool. Sooooo, Princeton Postdoctoral Fellow Alicia Soderberg got time on Swift to to observe SN2007uy in X-Ray light. These observations took place while she was in transit to give a talk on Supernovae, and she asked her colleage Edo Berger to watch the incoming data for her (the universe is fully of irony). While watching the data from SN2007uy, Edo noted a 5 minute long outburst of X-Rays from a different part of the galaxy. They quickly determined this outburst was most likely from a different supernovae in the first stages of going off. It turned out to be a Type Ibc supernova – a massive star collapsing into a neutron star. The X-Rays emitted were from the initial core collapse and energy release (confirming a theory on how these things worked – go theorists). The brightening that we normally see as the “first signs” of a supernova actually doesn’t occur until several days or weeks later. Never before have we seen the X-Rays that predate the optical brightening.

So this brings us to new ways to find Supernovae

The entire X-Ray burst only lasted about 5 minutes. This is a bit longer than most of gamma ray bursts. Sooo, if we are able to spot gamma ray bursts by just staring at sections of the sky with gamma ray telescopes (like Swift), we should be able to spot supernovae by looking for X-Ray bursts around the sky (with telescopes like Swift, which also works in UV as well). This may allow us to catch more and more supernovae just as they are popping off. These aren’t necessarily the type we most want to find (the illusive type Ia are the most loved of astronomers), but explosions are explosions, data are data and this is a new way to get data on explosions. So… Now we all know a new way to find supernovae in new wavelengths, and that’s just cool.

Clearly, we need more X-Ray telescopes. Wide field X-Rays are our friends. I don’t yet know the probabilities of detection, but I’m sure papers will come out soon. These are most likely to occur in galaxies rich in star formation, and can clearly be seen at least in the nearest 100 million light years of space.

This is such a wonderful discovery story. Science. Romance. Luck. There’s a movie here.

It’s been fun explaining it to my kids. My 13yo son asked which supernova really happened first. We know which we observed first. But which one happened first? That galaxy has had three supernovae observed in it since 1999. Could the explosion that we saw as SN2008d have occurred before the explosion that we saw as SN2007uy or even SN1999eh?

The Astronomy Picture of the Day for 18 January 2008 shows all three in NGC 2770.

“I don’t yet know the probabilities of detection, but I’m sure papers will come out soon.”

Oops…I just zapped off an email to the astronomycast address asking this very question. Hundreds of billions of galaxies, maybe 20 supernovae per century (on average) in each galaxy, probably at least half of those obscured. I can see a Drake-type equation coming together already. But I guess it all boils down to the limited number of telescopes focusing on a particular galaxy at the right moment in time. Dr. Alicia Sodeberg said in the NY Times that the odds were “unfathomable”. But is it as unfathomable as our national debt or as unfathomable as the number of electrons in the universe?

Looks like a v good post but I’m having problems reading it due to an advert

for Swinburn astronomy – is this just my machine? Cormac

Hi Professor,

I think it should be fixed now. So sorry. -P

wow astronomy is such an happening field, makes me wonder should have chosen astronomy for my M.Sc rather than plain old Physics- just got enrolled 3 days ago. oh well..

also talking of x rays, what happened to the Chandra xray telescope, havent heard much about it for quite a while now, whats it up to ….anybody know?

3.42 a.m

Calcutta,India

–ß–âˆâ€”Ç–∞–µ—à —å —ç—Ç–æ –∠–¥—É–º–∞–µ—à —å….