It’s summer, and that means I get to read fiction. The time I spend preparing for class during the semesters prevents me from often getting to enjoy the simple luxury of a book that I’m not either teaching from or reviewing. With my grades turned in, it times time to find a good paperback. Wanting to be a properly educated geek, I turned to , a list of books that was put together by a group of science faculty here at SIUE over good food and good beer. One of the books on the list that I haven’t read is Larry Niven’s

It’s summer, and that means I get to read fiction. The time I spend preparing for class during the semesters prevents me from often getting to enjoy the simple luxury of a book that I’m not either teaching from or reviewing. With my grades turned in, it times time to find a good paperback. Wanting to be a properly educated geek, I turned to , a list of books that was put together by a group of science faculty here at SIUE over good food and good beer. One of the books on the list that I haven’t read is Larry Niven’s “Ring World

“. While I’m only a little way’s in, I already have this feeling of “Wow, this was great science once, but that was a long time ago.” Just as astronomy text books can go out of date, science fiction books based on science can go out of date.

No significant spoilers ahead.

I’m only going to talk about one idea at this point, because I’m still reading. In Ringworld, one of the underlying plot ideas is that the dense stars at the center of the galaxy had undergone a chain reaction of nova, and the light from the nova are going to make life impossible for humans and aliens within the known star systems. At the time of its 1970 publication, astronomers didn’t know what was at the center of the galaxy.

Astronomers (not me, I wasn’t alive yet) knew it was a high-mass region, but we didn’t know how that mass was distributed. Some thought it was high density objects like white dwarfs, neutron stars, and stellar mass black holes. Others suspected a super massive black hole. It was also possible that it was a region of just a lot of normal stars. Because of the intervening dust and gas combined with the high density nature of the region, we just didn’t really have the ability to find out what was there.

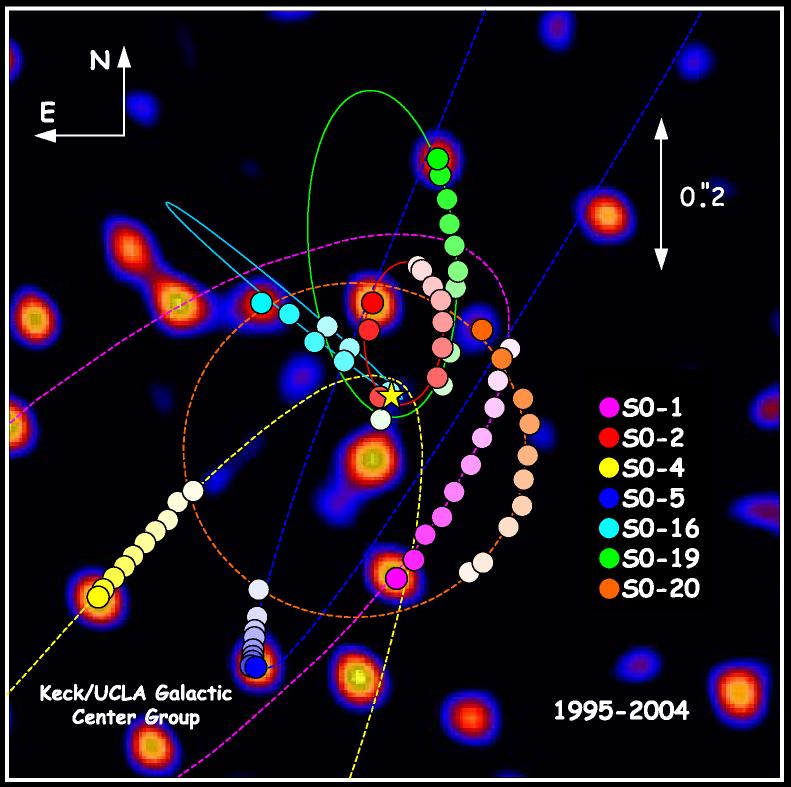

In the 1990s, however, technology was employed by UCLA astronomer Andrea Ghez to take high speed images of the center of the galaxy. These images were then aligned and stacked. By taking extremely short exposures, the noise introduced by the atmosphere was overcome. By stacking the images (adding together the light from successive frames), faint objects were drawn out of the darkness. In this case, Ghez and her team have been able to make out the orbits of series of stars (7 are highlighted in the image above) as they orbit an invisible point. This points observationally indicated mass of 2.6 million times the mass of the Sun is confined into such a small area that it has to be a black hole. Nothing else can be that dense.

So, Niven’s image of a dense region of exploding stars isn’t quite as possible as people might have thought in the 1960s (when he was writing it) and the 1970s (when people starting reading it).

That problem aside, Niven mentions gamma rays from supernova almost 30 years before we had the concept of gamma ray bursts being caused by certain subsets of supernova. I know he is just taking about gamma rays in general being given off during SN, but it does raise the question how how would a star be effected if it were in the a star cluster and took the fill blast of a gamma ray burst at close range. I’m going to have to think on that for a while, but it seems that if it were close enough (defining “enough” is the part where I’m going to need to think awhile) external heating could disrupt the normal energy transport mechanism and potential cause a burst nuclear burning in places where it normally would occur. These two effects could definitely disrupt a star in a “I just can’t make ‘er go, Cap’n” kind of way, but just Scotty could always repair the Enterprise, I suspect the star would rebound as well. But again, I need to think on this some more.

Still – neat science. The book makes you think, even if it also is showing some age. I’m sure I’ll have more to say as I continue to read this book and others this summer.

Hi Pamela.

The link you have in your posting to the list of books doesn’t go anywhere. Pity, because I would like to see what is on said list.

However, having read my share of science fiction in the past (and still continue today) I have to say that while my “expertise” in the field of astronomy and the sciences in general does not detract from a good story. Sure, I can read 2001 and – if I want to be critical – point out the flaws in the book that we now know exist. But it’s the same in any book you read: at the time, the author was going with either A) what he thought was correct, or B) it makes for good adventure. Just like knowing what we are currently finding on Mars shouldn’t detract from reading Wells’ War of the Worlds.

I recently picked up two books at a used store locally. One of them, A Beginner’s Star Book, was originally written in 1912 (my copy is the fourth edition from the late 1920’s) and back then they state “Jupiter has nine moons.” That is a far cry from the 62 Jupiter currently has. But it does not detract from the quality of the book; in fact, it makes it more enjoyable to read, in my opinion. It shows how much we have discovered over the years.

Happy reading.

Hi Kevin,

I’ve fixed the link. I’d love to hear your comments!

Just a quick note on what you said: I totally agree that a book van be good even when the science is wrong. I didn’t mean to say this was a bad book, only that our understanding has changed, and its facinating to see both how much good science when into writing the book and how much science has changed. At a certain level, good sci fi makes an archelogical record of our understanding of sciene and of the hopes and dreams of our culture.

I am still reading the book, still enjoying the book, but still having repeated “wow, that is not timeless” reactions. There are books that you read that could have been written in anywhen. This isn’t one. That’s okay though.

Cheers,

Pamela