NB: Space Carnival submissions due by Wednesday. Please submit!

NB: Space Carnival submissions due by Wednesday. Please submit!

Last month, I took this blog daily and gave it the tag line “Blogging one sidereal day at a time.” Everyday, as I read and explore astronomy, science and academics, I attempt to throw something on this little site and live up to that tagline. Today I launched a second, brand new shiny Earth and Sky blog, I’m going to work to bring them, at least once a week, the best of what I find in my daily astronomy-related explorations (which I will also bring to you). This translates into a new tag line: Exploring the sky, one sidereal day at a time.

One of my silly little disappointments with Star Stryder is that no one has asked me what sidereal day means. This could just reflect how skilled everyone has gotten at googling answers, or perhaps Wikipedia has made us all just a bit wiser with its big collective brain. Whatever the reason, I feel like a little kid running around saying, “I learned all about platypuses today,” only to be asked, “What did you learn about the Louisiana Purchase?”

You know, I don’t want to talk about the Louisiana Purchase. I want to talk about platypuses.

Well, actually, I’d like to talk about sidereal days.

If you are given to watching the sunset and wishing on the first star (which may be a planet) you see each night, you may notice that as the constellations wink into visibility they are in a slightly different place each evening twilight. This change occurs for two reasons: sunset occurs at a different time each night, and the alignment between the Sun, Earth and stars is also a little different each night.

I’m going to wait to discuss this first, sunset-time changing problem, until next week, and just take on this change of alignment, sidereal day causing, problem for now.

Let’s start by imagining December 12. On this cold (northern) winter’s day, a person watching the horizon’s of sunrise and sunset would notice the eastern edge of the constellation Ophiuchus just rising in the east at sunrise and the western edge of Ophiuchus just setting in the west at sunset. This means that on December 12, the Sun is planted between us and the often ignored constellation of the Serpent Bearer. If you’re not particularly fond of snakes, this probably sounds like a good place for the Sun to be.

Now consider what the sky will look like 6 months later on a languid day in June – say on June 12 – and look again through our horizon watcher’s eyes. On this probably hot and hazy day, the bull Taurus will appear to poke above the horizon at sunrise and will follow the Sun below the horizon in the evening. Thus, in June, the Sun is placing itself between us and the Bull.

What is actually changing between these two circumstances is how the Earth, Sun and stars are aligned. Let’s extend our constellations as living breathing heros and monsters analogy a bit, and imagine the 12 commonly known zodiacal signs + Ophiuchus arrayed menacingly around the edge of a giant stadium. Now imagine we are huddled together in the center with a very fat yellow rodeo clown. While most rodeo clowns are quick and nimble, this particular clown is actually just a big plastic blowup clown who is nailed to the center of our arena. As we stand, arms length away from our plastic clown, in one location we can see Ophiuchus leering at us over the clown’s shoulders. If we turn our back on the Clown we now find ourself face to face with the red-eye’d Taurus. If we move 180 degrees around the clown, in a mad clockwise dash, we’ll find ourselves peering over the clown’s shoulder at Taurus, but now our back is left exposed to Ophiuchus, and when we put our back to the clown we are face to face with a hero and his snake.

Just as the monster and hero the clown blocked from us varied with our position, the constellation the Sun appears within depends on where our planet is located within its orbit. Each day we move one giant, frantic step clockwise, as the Sun appears to step from Sagittarius to Capricorn to Aquarius as the months move from January to February to March.

So now you know the story of how the Sun moves through the stars. But I haven’t exactly touched on “sidereal day.”

In our day-to-day life we measure our moments relative to the Sun. From midnight-to-midnight we measure one day in a way that is equal to the 24 hour average length between sun-high noon and sun-high noon. But, those of us who study the stars are in need of a different measure of time, one that instead measures the span of time from star-high moment to star-high moment.

The 24 hour day gives us just enough time for the Earth to start out with your nose facing the Sun, and to get rotated through more then 360 degrees as the Earth steps clockwise around the Sun and rotates back to placing you nose-to-Sun once again.

With the stars, not so much rotation is required. They stay in place, and a 360 degree rotation is all that is ever needed.

Consider the star Caph in Cassiopeia. This bright star marks the end of the short arm of the W that is named after a queen. This star lies right off the zero hour line that marks the beginning of time on the sky. If I measure the minutes from Caph passing through the top of the sky – crossing the meridian – to its return to that same high-sky position, I’ll count 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds. This span of time is called one sidereal day. The slight differences between a solar measured day and a sidereal day comes from the extra distance the Earth must rotate to point itself back at the Sun from its new position.

Looking at my sidereal time keeping clock, I know that 9 minutes into a new day, Caph passes through its highest position in the sky. I know that Betelgeuse will always pass through its personal high point at 5:55 into the day. Every sidereal day, the stars will always find themselves arrayed in the same way and the same sidereal moment.

It is only the Sun that forces our view to change. So one solar day at a time I live my life, in our Sun driven society, while the stars make their way one sidereal day at a time through our skies.

So, for anyone who cares to ask, when I say I’m blogging one sidereal day at a time, it means my Star Stryder sidereal-daily blog will average 366.24 posts a year instead of the solar days average 365.24 posts per year.

I did indeed google sidereal day and hit wikipedia…

Although your explanation makes more sense.

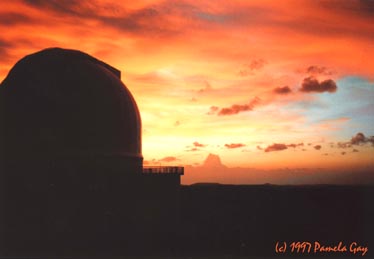

PS: I’ve seen that picture before… wasn’t it on your webpage you had at the uni in tx?

But… I don’t want to talk about sidereal days, I want to talk about pair-production instability supernovae, or black holes, or whether we’ll be toasted by radiation when Eta Carinae goes ‘boom’… 🙂

Seriously though, it’s a tough nut to crack to know exactly how technical to get when talking with people about astronomy. Last time I participated in a public program at the local observatory, I was in the midst of my spiel, when one of the ‘public’ asked (in a thick accent) if he could move my scope to look at something else. It turns out he was an astronomy professor from Italy, and lives near Padua! Yet, in the same night someone else expressed amazement that the stars were outside the solar system!

Hi Astrogeek,

You really never know who might be in the crowd, but if you talk for the first time Sky & Tel reader (someone who wants to know but is still coming up to speed), you are likely to not annoy too many folks. The wise ones will recognize what you are up to, and the unwise ones will hopefully feel free to ask questions.

I have to admit that I am highly amused by how differently I get treated as a member of the press versus as a researcher. When people see a press name badge they often explain things in plain english, slowly, and ask questions to make sure they are clear. If I’m in a hurry, I’ll often admit that I have a PhD and encourage them to jump to the meat, but sometimes this backfires because they’ll assume a level of jargon knowledge that I just don’t have if they’re not in my sub-field. The transition is really amazing to watch.

So where did he move your scope?

I’ll count 23 hours 56 minutes and 4.1 seconds. This span of time is called one sidereal day.

-pam

excuse the ignorant public here..

So is that how you calibrate a telescope by using

that time as a frame of reference?

Is there a good software program you can recommend for directing an amatuer stargazer? How do you calibrate it when starting up?

Sorry about the dumb questions doc.

Sorry Pamela. I know what a sidereal day is, so I didn’t have to ask. In fact I used it a few days ago, when someone on a forum I frequent said they would take a year off from work. I asked which type of year, just to be smart/sarcastic.

Hi HoosierHoops, There is an online sidereal clock here.

Most observatories will have some sort of a radio clock that gets the time from National Institute of Standards and Technology and the US Naval Observatory. These clocks then get (either via user input or GPS, which would also get the time) the users location and does the math to output the local sidereal Time.

Put simply: Astronomers either pop a web window or buy a device that sits on their desk 🙂

And Kevin – I’m going to have to borrow that line 😉

Hi Pamela.

He wanted to see if it could pick out M44, but the conditions weren’t good, too much moonlight, too much wind.

Funny story about the whole sidereal thing… I’m working on a paper about the technical advances that led to better asteroid detection/tracking (well, I WAS writing the paper, and I WILL again once I’m done with this response, but I digress…)

Anyway… I was doing this research and came across “sidereal” and wondered to myself, “I wonder what sidereal is?” and looked it up.

So… When I got to your page and saw “One sidereal day at a time…” I kinda giggled (not outloud… my daughter’s here and Marine Dad’s aren’t supposed to giggle) and said to myself, “I know what that means!!”

Thanks, Dr. Pam, for giving me something else to do when I’m SUPPOSED to be working on my paper… =)